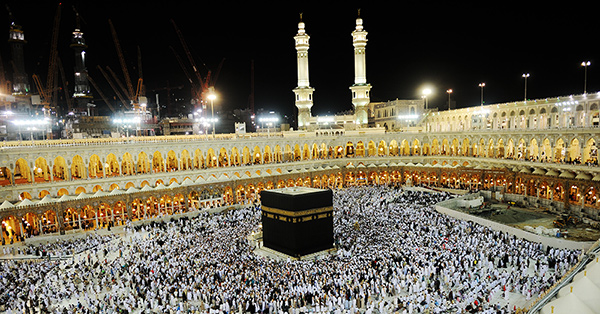

The fifth Pillar of Islam is the pilgrimage to Makkah and its surroundings known as Hajj. All Muslims are obligated to make Hajj once in their lifetimes if they can afford it and are otherwise able to do so.

The Hajj is made from the eighth to the twelfth of the Islamic month of Dhul-Hijjah. Muslims travel from all over the world to perform Hajj. The rituals are themselves simple, but the amount of walking necessary, the hot climate, and the crowds make the Hajj a rigorous exercise in faith. Still, between 2 and 3 million people perform Hajj every year, and millions more yearn to do so.

To perform the Hajj, pilgrims enter a state of consecration known as ihram. In this state they may not clip their nails, cut or pluck any hair, or have any sort of sexual contact. Male pilgrims wear special clothes consisting of two seamless strips of cloth, one covering the back and shoulders, the other covering from the waist to the knees. Female pilgrims can wear ordinary clothing that covers everything but the face and hands.

The rituals of Hajj date back to the time of Prophet Ibrahim (Abraham) and commemorate his willingness to sacrifice his only son, Ismail (Ishmael). During the days of Hajj, the pilgrims attempt to forget all but their most basic worldly needs and to focus their attention and devotion on Allah Alone. Upon arriving in Makkah, the pilgrims first circumambulate the Kabah seven times in a ritual known as Tawaf. This ritual reminds the pilgrims that Allah (God) should be the focus and center of their lives.

The Symbolism and Related Rites of the Kabah The next ritual is Sai, which is walking back and forth seven times between the hillocks named Safa and Marwah. This commemorates the search for water made by Hajar (Hagar) when Prophet Ibrahim (peace be upon him) left her and her infant son Ismail (peace be upon him) in the desert. On Dhul-Hijjah 8, pilgrims head to Mina, where they spend the day supplicating Allah.

Early the next morning they go to Arafah (or Arafat). They spend the day supplicating Allah and begging for His forgiveness. Many stand on the Mount of Mercy to supplicate, though this is not necessary. When the sun sets on the Day of Arafah, the pilgrims’ sins are forgiven. After sunset the pilgrims move on to Muzdalifah, where they spend the night and collect pebbles to be used in the next ritual. The next morning, Dhul-Hijjah 10, is the Day of Sacrifice.

Most pilgrims slaughter a sheep or goat, and the meat is distributed to the poor. (Muslims who are not on Hajj also slaughter that day, which is known as Eid Al-Adha.) The ritual commemorates Ibrahim’s willingness to sacrifice his son Ismail (peace be upon them both) and Allah’s provision of a ram as a substitute sacrifice. But before slaughtering, the pilgrims go to throw pebbles at the stone pillars known as Al-Jamarat.

This ritual commemorates Ibrahim’s stoning of Satan when the latter tried to tempt him to disobey Allah. After this, the pilgrims cut or shave their hair (women cut off only a small amount) and return to Makkah to repeat Tawaf and Sai.

They sleep at Mina and repeat the stoning of the pillars on the next two days. A final Tawaf before leaving Makkah completes the Hajj. Many pilgrims also go to Madinah before or after Hajj in order to pray in the Prophet’s Mosque and visit his grave, although this visit to Madinah is not necessary. The above is only a summary. There is some variation in the performance of Hajj, depending on whether the individual pilgrim chooses to also performUmrah (often known as the lesser pilgrimage) beforehand and whether this will be while in one prolonged state of ihram or two separate ones for `Umrah and Hajj. By AElfwine Mischler

Hajj: The Journey of a Lifetime (Part 1) The Day of Arafah and its Preparation

The hajj, or pilgrimage to Makkah, a central duty of Islam whose origins date back to the Prophet Abraham, peace be upon him, brings together Muslims of all races and tongues for one of life’s most moving spiritual experiences. For fourteen centuries, countless millions of Muslims, men and women from the four corners of the earth, have made the pilgrimage to Makkah, the birthplace of Islam. In carrying out this obligation, they fulfill one of the five “pillars” of Islam, or central religious duties of the believer. Muslims trace the recorded origins of the divinely prescribed pilgrimage to the Prophet Abraham.

According to the Quran, it was Abraham who, together with Ishmael, built the Ka’bah, “the House of God”, the direction toward which Muslims turn in their worship five times each day. It was Abraham too who established the rituals of the hajj, which recall events or practices in his life and that of Hagar and their son Ishmael. In the chapter entitled “The Pilgrimage”, the Quran speaks of the divine command to perform the hajj and prophesies the permanence of this institution: “And when We assigned for Abraham the place of the House, saying ‘Do not associate anything with Me, and purify My House for those who go around it and for those who stand and bow and prostrate themselves in worship.

And proclaim the Pilgrimage among humankind: They will come to you on foot and on every camel made lean by traveling deep, distant ravines.’” (Al-Hajj 22:26-27) Prophet Muhammad By the time the Prophet Muhammad, peace be upon him, received the divine call, however, pagan practices had come to muddy some of the original observances of the hajj.

The Prophet, as ordained by God, continued the Abrahamic hajj after restoring its rituals to their original purity. Furthermore, Muhammad himself instructed the believers in the rituals of the hajj. He did this in two ways: by his own practice, or by approving the practices of his companions.

This added some complexity to the rituals, but also provided increased flexibility in carrying them out, much to the benefit of pilgrims ever since. It is lawful, for instance, to have some variation in the order in which the several rites are carried out, because the Prophet himself is recorded as having approved such actions.

Thus, the rites of the hajj are elaborate, numerous and varied; aspects of some of them are highlighted below. The hajj to Makkah is a once-in-a-lifetime obligation upon male and female adults whose health and means permit it, or, in the words of the Quran, upon “those who can make their way there.” It is not an obligation on children, though some children do accompany their parents on this journey.

Hajj History Before setting out, a pilgrim should redress all wrongs, pay all debts, plan to have enough funds for his own journey and for the maintenance of his family while he is away, and prepare himself for good conduct throughout the hajj.

When pilgrims undertake the hajj journey, they follow in the footsteps of millions before them. Nowadays hundreds of thousands of believers from over 70 nations arrive in Makkah by road, sea and air every year, completing a journey now much shorter and in some ways less arduous than it often was in the past. Till the 19th century, traveling the long distance to Makkah usually meant being part of a caravan.

There were three main caravans: the Egyptian one, which formed in Cairo; the Iraqi one, which set out from Baghdad; and the Syrian, which, after 1453, started at Istanbul, gathered pilgrims along the way, and proceeded to Makkah from Damascus. As the hajj journey took months if all went well, pilgrims carried with them the provisions they needed to sustain them on their trip.

The caravans were elaborately supplied with amenities and security if the persons traveling were rich, but the poor often ran out of provisions and had to interrupt their journey in order to work, save up their earnings, and then go on their way.

This resulted in long journeys which, in some cases, spanned ten years or more. Travel in earlier days was filled with adventure. The roads were often unsafe due to bandit raids. The terrain the pilgrims passed through was also dangerous, and natural hazards and diseases often claimed many lives along the way.

Thus, the successful return of pilgrims to their families was the occasion of joyous celebration and thanksgiving for their safe arrival.

Lured by the mystique of Makkah and Madinah, many Westerners have visited these two holy cities, on which the pilgrims converge, since the 15th century.

Some of them disguised themselves as Muslims; others, who had genuinely converted, came to fulfill their duty. But all seem to have been moved by their experience, and many recorded their impressions of the journey and the rituals of the hajj in fascinating accounts.

Many hajj travelogues exist, written in languages as diverse as the pilgrims themselves. Hajj Rites The pilgrimage takes place each year between the 8th and the 13th days of Dhul-Hijjah, the 12th month of the Muslim lunar calendar. Its first rite is the donning of the ihram.

The ihram, worn by men, is a white seamless garment made up of two pieces of cloth or toweling; one covers the body from waist down past the knees, and the other is thrown over the shoulder. This garb was worn by both Abraham and Muhammad. Women dress as they usually do.

Men’s heads must be uncovered; both men and women may use an umbrella. The ihram is a symbol of purity and of the renunciation of evil and mundane matters. It also indicates the equality of all people in the eyes of God. When the pilgrim wears his white apparel, he or she enters into a state of purity that prohibits quarreling, committing violence to man or animal and having conjugal relations. Once he puts on his hajj clothes the pilgrim cannot shave, cut his nails or wear any jewelry, and he will keep his unsown garment on till he completes the pilgrimage.

A pilgrim who is already in Makkah starts his hajj from the moment he puts on the ihram. Some pilgrims coming from a distance may have entered Makkah earlier with their ihram on and may still be wearing it. The donning of the ihram is accompanied by the primary invocation of the hajj, the Talbiyah: “Here I am, O God, at Your Command! Here I am at Thy Command! You are without associate; here I am at Your Command! To You are praise and grace and dominion! You are without associate.”

The thunderous, melodious chants of the Talbiyah ring out not only in Makkah but also at other nearby sacred locations connected with the hajj.

On the first day of the hajj, pilgrims sweep out of Makkah toward Mina, a small uninhabited village east of the city. As their throngs spread through Mina, the pilgrims generally spend their time meditating and praying, as the Prophet did on his pilgrimage. During the second day, the 9th of Dhul-Hijjah, pilgrims leave Mina for the plain of Arafat where they rest. This is the central rite of the hajj. As they congregate there, the pilgrims’ stance and gathering reminds them of the Day of Judgment.

Some of them gather at the Mount of Mercy, where the Prophet delivered his unforgettable Farewell Sermon, enunciating far-reaching religious, economic, social and political reforms. These are emotionally charged hours, which the pilgrims spend in worship and supplication.

Many shed tears as they ask God to forgive them. On this sacred spot, they reach the culmination of their religious lives as they feel the presence and closeness of a merciful God. Western Experience The first Englishwoman to perform the hajj, Lady Evelyn Cobbold, described in 1934 the feelings pilgrims experience at Arafat: “It would require a master pen to describe the scene, poignant in its intensity, of that great concourse of humanity of which I was one small unit, completely lost to their surroundings in fervor of religious enthusiasm.

Many of the pilgrims had tears streaming down their cheeks; others raised their faces to the starlit sky that had witnessed this drama so often in the past centuries. The shining eyes, the passionate appeals, the pitiful hands outstretched in prayer moved me in a way that nothing had ever done before, and I felt caught up in a strong wave of spiritual exaltation.

I was one with the rest of the pilgrims in a sublime act of complete surrender to the Supreme Will which is Islam.” She goes on to describe the closeness pilgrims feel to the Prophet while standing in Arafat: “…as I stand beside the granite pillar, I feel I am on Sacred ground.

I see with my mind’s eye the Prophet delivering that last address, over thirteen hundred years ago, to the weeping multitudes. I visualize the many preachers who have spoken to countless millions who have assembled on the vast plain below; for this is the culminating scene of the Great Pilgrimage.”

The Prophet is reported to have asked God to pardon the sins of pilgrims who gathered at Arafat, and was granted his wish. Thus, the hopeful pilgrims prepare to leave this plain joyfully, feeling reborn without sin and intending to turn over a new leaf. By Nimah Nawwab